How Do Supply and Demand Affect the Value of Money?

Let’s start with some basic market dynamics. The price of a good is set by demand and supply, right? If there is a lot of demand for a good and little supply its price will be higher, if there is a lot of supply and less demand for it, its price will be lower.

The same rules apply for our money, with the difference to consumption goods, that it isn’t consumed meaning the quantity of money that is in circulation usually does not get less. Okey maybe some bank notes get destroyed from time to time let’s say in a fire or whatever but well this is as you will see later really an insignificant small part of the total supply.

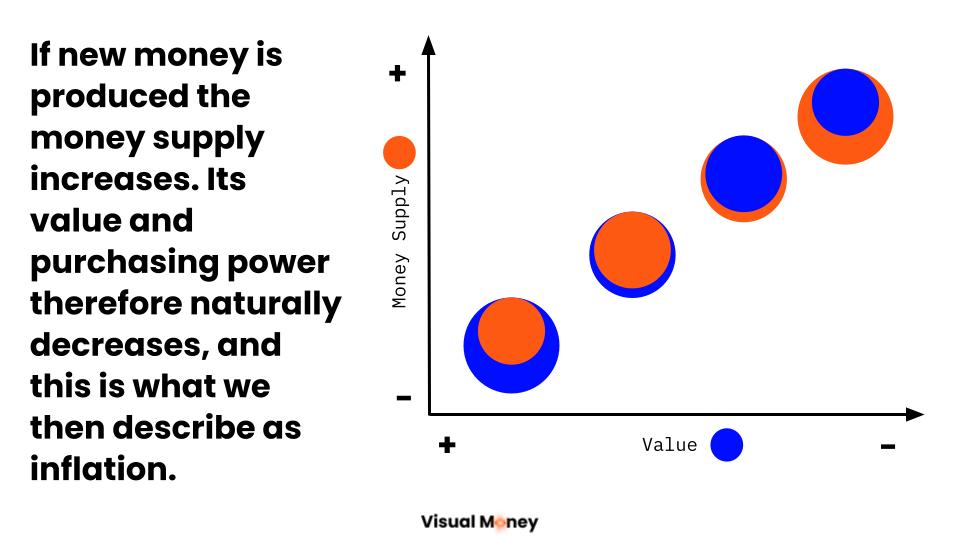

Why Does Increasing the Money Supply Lead to Inflation?

So, if new money is produced the money supply will increases. Its value therefore naturally decreases, and this is what we then describe as Inflation. “The money supply is inflating”. Prices going up is just a consequence, the root cause is in the money supply. We will dig deeper into this in a separate post about inflation.

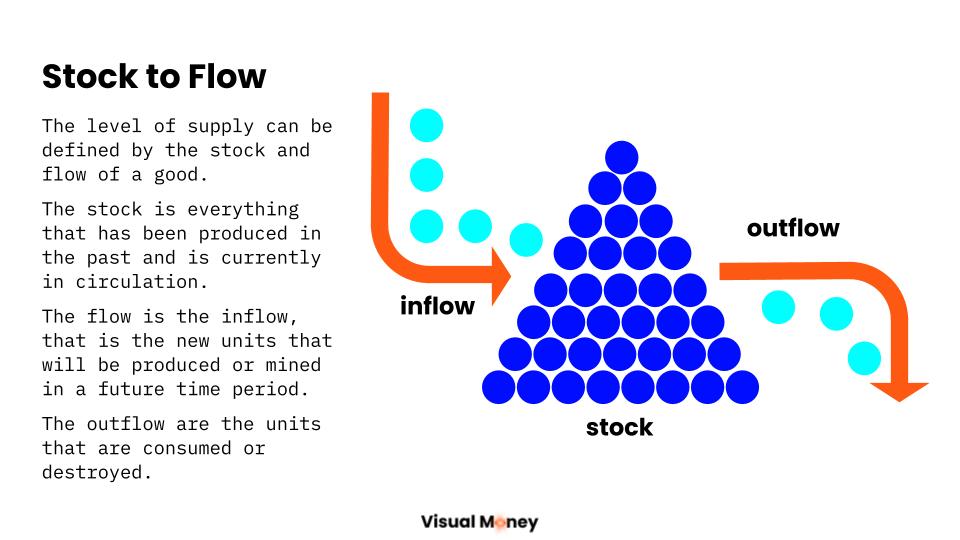

The level of supply can be defined by the stock and flow of a good. The stock is everything that has been produced in the past and is currently in circulation. The flow is the inflow, that is the new units that will be produced or mined in a future time period and outflow, namely the units that are consumed or destroyed.

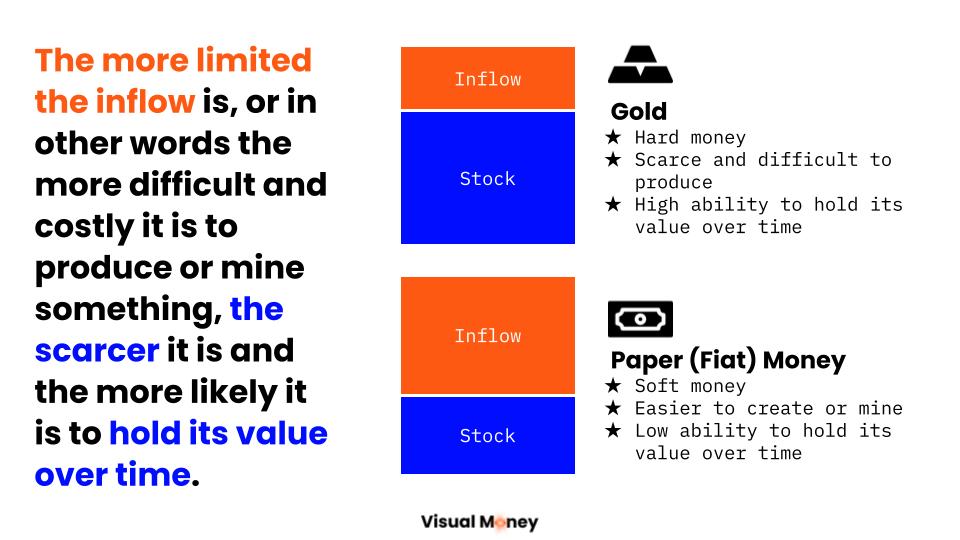

The more limited the inflow is, or in other words the more difficult and costly it is to produce or mine something the scarcer it is and the more likely it is to hold its value over time.

Let’s put it into an example. Imagine the production of jeans, before they had to be produced fully by hand, production was slower and more costly, less units were available for an increasing demand, only those who bid the most money for it were able to acquire a pair. Their value was therefore higher. Later, with machine-based production, they were easier, faster, and cheaper to make. Supply increased and an ever-increasing share of demand could be covered, and people could acquire them for less money. Their value decreased over time because the inflow increased.

We can apply the same principle to money. We often talk about hard or soft money when we describe its ability to hold its value over time. Hard money is scarce and difficult to produce and therefore holds its value better than soft money that is easier to create or mine and its supply therefore easier to increase.

What is the Stock-to-Flow Ratio and Why Does it Matter?

The so-called Stock to Flow Ratio can be used to rate the level of hardness. It is the existing stock divided through new units produced in a period of time.

When it comes to Gold for example its current stock are approximately 190000 tonnes and during the last years round about 3000 tonnes of new gold have been mined every year, meaning the stock to flow ration would be about 190000 tonnes/3000 tonnes = 63. Gold is scarcest metal in the world and therefore has a very high stock to flow ratio.

What are the Different Types of Money Supply?

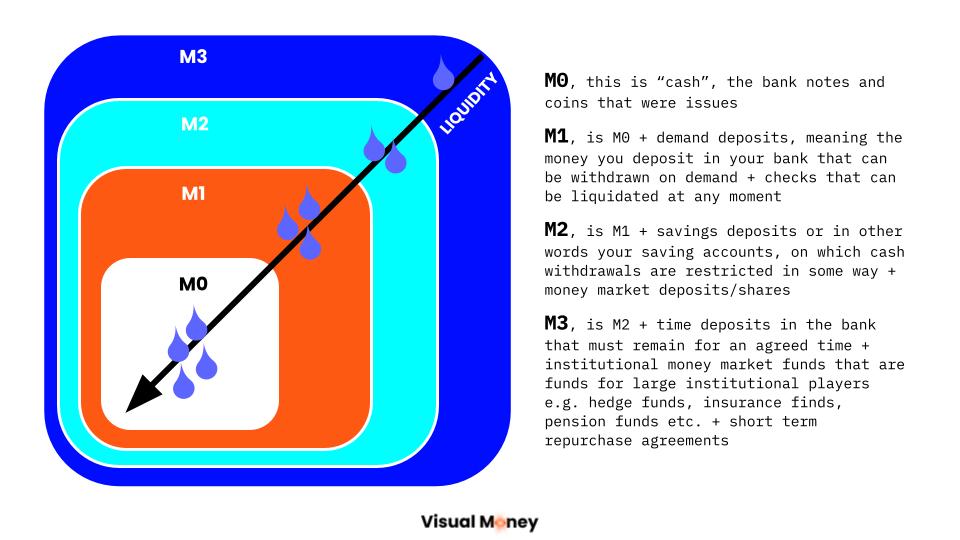

So let’s have a look into the money supply in specific, which is the amount of money circulating in the economy. The money supply actually not only consist of the bank notes and coins issued but of 4 “concepts” of money, also called monetary aggregates, that are distinguished by the level of liquidity. Liquidity basically means how easy something can be converted into cash to pay for something else.

- M0, this is “cash” the bank notes and coins that were issues

- M1, is M0 + demand deposits, meaning the money you deposit in your bank that can be withdrawn on demand + traveller’s checks that can be liquidated at any moment

- M2, is M1 + savings deposits or in other words your saving accounts, on which cash withdrawals are restricted in some way + money market deposits/shares M3, is M2 + time deposits in the bank that must remain for an agreed time + institutional money market funds that are funds for large institutional players e.g. hedge funds, insurance finds, pension funds etc. + short term repurchase agreements

How Do Central Banks Control the Money Supply?

This money supply is regulated by the Central Banks. They use different instruments to regulate the money supply, meaning to decrease but mainly increase it.

- Printing money: Central banks like the Federal Reserve in the US or the European Central Bank can issue money and increase the money supply by literally printing new money bills, though this is not the common way anymore. Modern Central banks issue money by digitally creating new money balances and crediting them to the accounts of banks. Banks then again can issue credits to consumers to bring the new money into the economy.

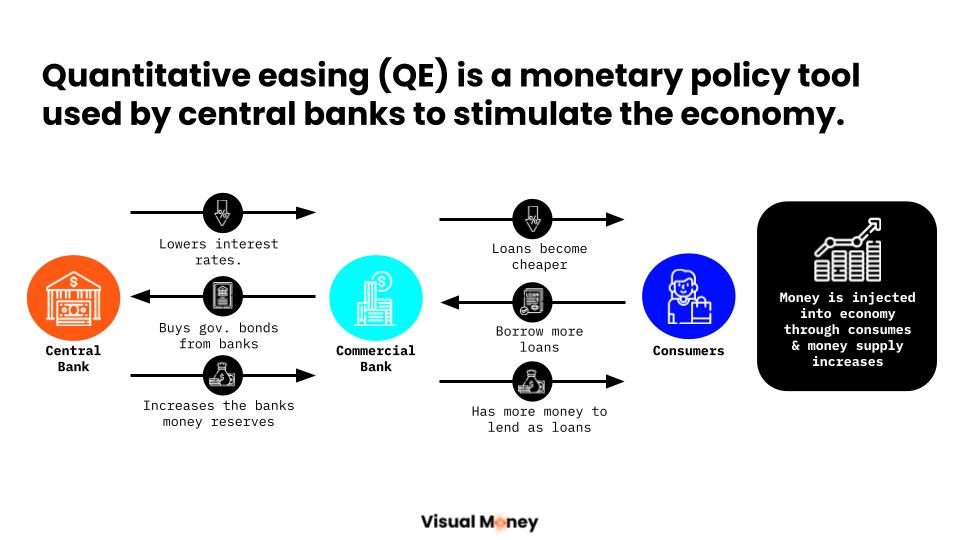

- Quantitative Easing: Central banks can also inject more liquidity (cash) into an economy by buying longer-term securities as for example government bonds (a bond is basically loan from an investor to a borrower like a company or government) and other financial assets (e.g. stocks, corporate bonds etc.)

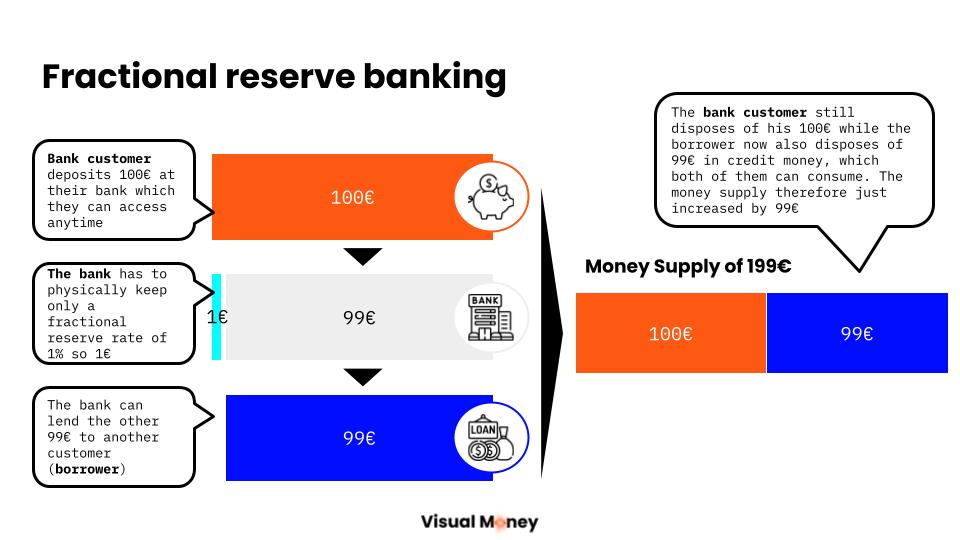

- Fractional reserve banking: fractional reserve banking means that the banks only have to keep a fraction (%) of the money deposited in the bank as minimum reserves. The rest of the money can be handed out as credits to others. The fractional reserve rate is determined by each central bank. In 2012 the ECB lowered this rate to 1%, meaning your bank must keep only 1% of the money you deposited in your account. So, if you deposited 1000€, your bank only has to keep 10€ in their reserves the other 990€ can be handed out as credits. This creates a money multiplier effect since you still own the 1000€ in your account and can buy with them whatever you want and the person who took the 990€ credit also has this money immediately available for consumption.

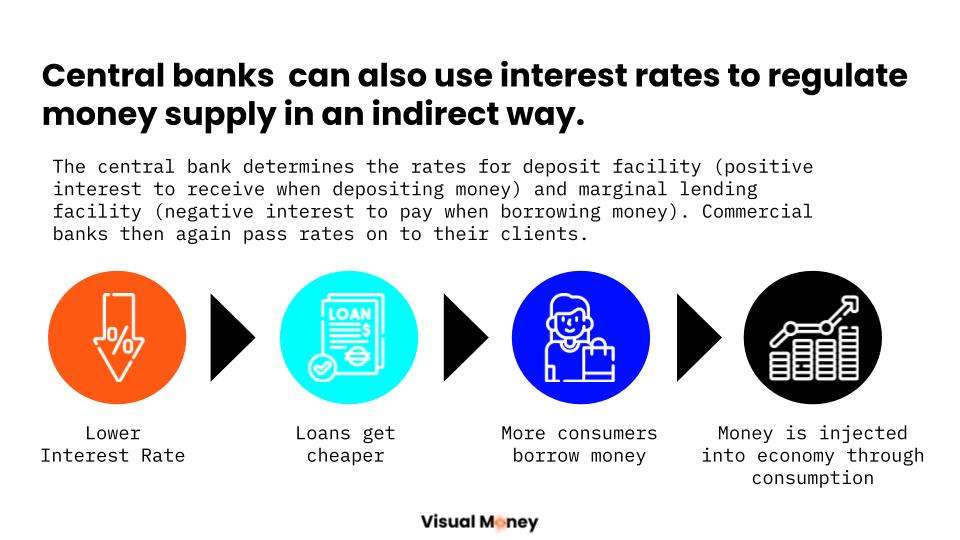

- Central Bank interest rates: The CBs can also use interest rates to regulate money supply in an indirect way. The CB determines the rates for deposit facility (positive interest to receive when depositing money) and marginal lending facility (negative interest to pay when borrowing money). Commercial banks then again pass rates on to their clients. So, for example when deposit facility rates are low you will receive little interest for the money you have in your bank account, so you are incentivized to spend it or buy assets. When marginal lending facility rates are low you will have to pay little interest when you take on a credit, you are incentivized to borrow “cheap” money to again spend it or invest it in assets.

In conclusion, understanding how these mechanisms influence the money supply and inflation is essential to making informed decisions for your financial future.